In the 1970s, Mary Hemming AO was in charge of the outpatient pharmacy at Royal Melbourne Hospital. Dermatology patients would queue for hours, she recalls, for the diverse creams and ointments prescribed by their specialists.

“Each one had to be made up individually, and I thought, ‘This is crazy’, because a lot of the preparations were only marginally different. So I spoke to the dermatology clinic and they came up with a standardised list of preparations that all the doctors agreed on.”

As Hemming began building hospital-wide relationships, it became clear to her and others that a similar approach could help with many prescribing issues. So it seemed a natural development when prescribing guidelines were suggested as a way of tackling the emerging problem of antibiotic resistance. The Antibiotic Guidelines were published in 1978, initially to guide junior doctors, as a little book designed to fit inside a doctor’s white coat pocket.

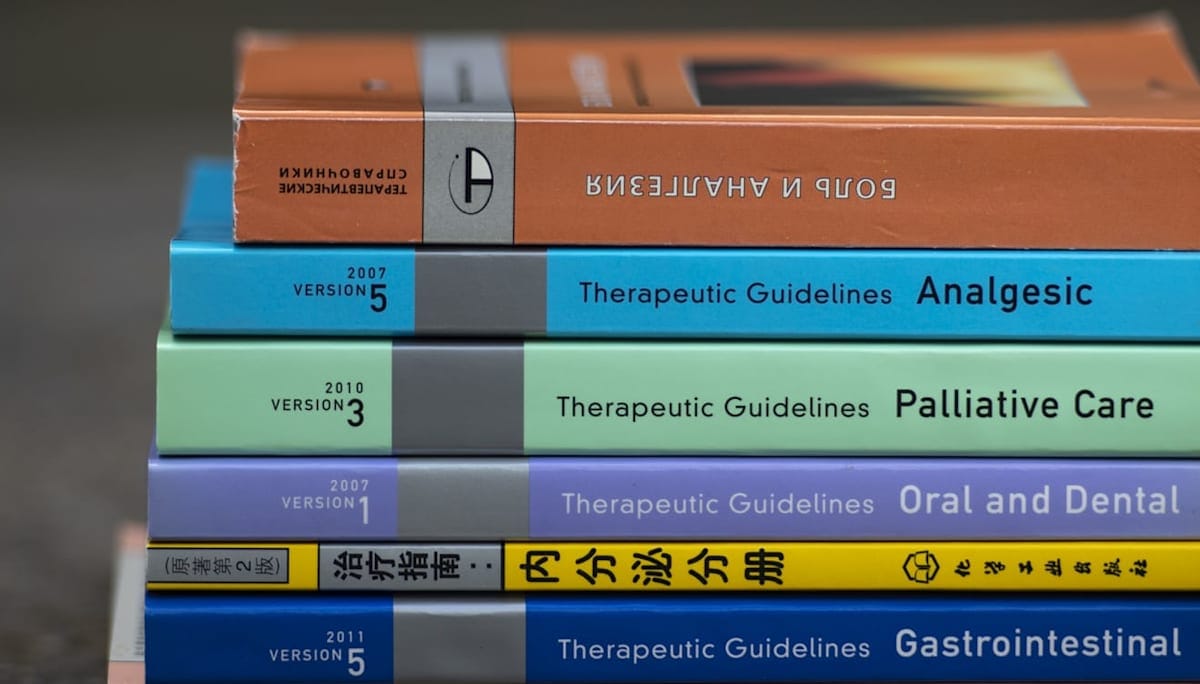

Victoria’s health department appointed Hemming to run a ministerial advisory committee to scrutinise drug use in public hospitals. By 1994, guidelines on optimising the use of analgesic, psychotropic, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and respiratory drugs had been published. They were adopted nationwide for use not only in hospitals, but also in community medical practices.

"I realised you couldn’t do a lot by yourself, but together with people from different disciplines and professions, you could really influence the system.”

“It just sort of grew and grew,” says Hemming, who graduated in 1965 from the Victorian College of Pharmacy, which later became part of Monash University.

In 1996, she and colleagues set up a not-for-profit organisation, Therapeutic Guidelines Limited (TGL), independent of government and the pharmaceutical industry, and self-funding from sales and subscriptions. Hemming was founding CEO. Australia’s leading experts contributed specialist knowledge based on the latest international literature, and an editorial team ensured the guidelines were clear, succinct and contextualised for everyday use.

Nowadays, Therapeutic Guidelines – covering 17 medical disciplines and thousands of drugs – is embedded in the culture of clinical practice, consulted by GPs, hospital doctors, pharmacists, and medical, pharmacy and nursing students. It’s available as an integrated online resource and an app, both called ‘eTG complete’.

Thanks to the guidelines, Hemming believes “the patients of Australia are managed pretty well”. TGL has donated free copies to developing nations, and has helped a number of countries, particularly in the Pacific, to adapt the guidelines to local conditions.

Hemming retired in 2012, but she remains on the board of Therapeutic Guidelines Foundation, a charity established by TGL to promote the quality use of medicines in low and middle-income countries, and to train local health professionals to develop their own guidelines.

With international colleagues, she’s also founded the International Society to Improve the Use of Medicines, which she calls “a platform for people to work together on different issues – not just drug guidelines, but policy, education and community-based activities”. The society held its first international conference in Bangkok last January.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, TGL made the guidelines free for healthcare workers.

With a rising number of drugs on the market, an independent, reliable source of information is more important than ever, Hemming says. The guidelines have proved particularly useful in rural and remote Australia. “People doing locums in remote areas would email me saying they’d be lost without them. It’s not easy to get a second opinion in the middle of nowhere.”

A former federal president of the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia, Hemming maintains close ties with Monash’s Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Reflecting on her legacy, she says: “I never set out to change the world – I just used to see problems and think, ‘How do you fix them?’ And I realised you couldn’t do a lot by yourself, but together with people from different disciplines and professions, you could really influence the system.”

140 years of the Victorian College of Pharmacy

In 2021 the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences will be celebrating 140 years of the Victorian College of Pharmacy. If you'd like to know more about the planned celebrations please contact us.